Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

It all began on May 27, 1956 when two Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University boarded a local city bus. When Wilhelmina Jakes and Carrie Patterson boarded the bus, they sat in the only two seats available that happened to be in the whites-only section. They were asked to stand or leave the bus without a refund. When they refused, they were jailed for inciting a riot and released on bond later that same day. These events led to a boycott of the buses in the Tallahassee community. Gradually, the Tallahassee Bus Boycott and its organizers began to see some of their demands met with African Americans being hired as bus drivers. The boycott ended on December 22, 1956 and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation on city buses was unconstitutional.

Chicago Manual of Style

Florida Memory. "The Tallahassee Bus Boycott." Floridiana, 2022. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/259734.

MLA

Florida Memory. "The Tallahassee Bus Boycott." Floridiana, 2022, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/259734. Accessed January 31, 2022.

APA

Florida Memory. (2022). The Tallahassee Bus Boycott. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/259734

The I-75 corridor runs the length of the State of Georgia. It is, without question, a primary roadway through, to and within our State. Given its level of importance, maintenance, redesign and reconstruction must occur. When such design and construction activity is considered, the communities in and around the Interstate must be considered too. The Pleasant Hill community in Macon, Georgia is one such community. For nearly fifteen (15) years there had been discussion about the work that needed to happen at Interstates 16 and 75 in and around Macon. The Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) understood that it needed to enlist the assistance of its internal departments as well as the external Macon community, to ensure that any work done was done in a manner that respected both the geographic and cultural environment of this historically black community that was once the childhood home of Little Richard.

In keeping with its mission of Creating a Culture of Collaboration and Innovation, the GDOT was both collaborative and innovative in making necessary improvements to the Interstate and the community it serves. GDOT recognized and made good on its duty to go beyond “doing no harm” to making a positive investment in the community.

View Keeping the Hill Pleasant- Macon’s Oldest African American Community - GDOT’s I-16/I-75 Mitigation Plan for Macon’s

Pleasant Hill Community Below:

Alabama

Recognizing Mae C. Jemison of Decatur, AL as the first black woman selected to be an astronaut by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). On September 12, 1992, over five years after joining NASA, Jemison became the first African-American female to go into space. She served an eight-day voyage upon the Space Shuttle Endeavour.

Kentucky

Recognizing Garrett Morgan of Kentucky who some transportation leaders call “The Father of Transportation Technology” as the inventor of the traffic light. Morgan first tested his traffic light in Cleveland in 1922. Morgan’s hand-cranked semaphore traffic management device was in use throughout North America. It was eventually upgraded with the automatic red-green-yellow-and green-light traffic signals currently used around the world. In 1963, the United States Government awarded Morgan a commendation for his traffic signal.

Mississippi

Recognizing Jessie L. Brown of Hattiesburg, MSas the first African American naval aviator in the United States Navy in 1948. Ensign Jesse L. Brown was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his Korean Ware combat service.

Tennessee

Recognizing Geraldetta Dozier as the first Black woman to operate a bus in Knoxville in 1976. This venture started as way to help a single mother support her family but led to breaking down barriers and helping more Black women enter the workforce in America. Her career would span 26 years driving the Knoxville Area Transit bus logging more than 2 million miles and winning several safe driving awards.

South Carolina

Recognizing South Carolina native, astronaut Dr. Ronald E. McNair, a native of Lake City, SC who was one of the first African American astronauts at NASA. Dr. McNair “earned his Ph.D. from Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1976 at the age of 26. In addition to academic achievements he received three honorary degrees, as well as numerous fellowships and commendations. … he was an attentive husband, loving father, a 6th degree black belt in karate, and an accomplished jazz saxophonist. … Selected as an astronaut candidate by NASA in 1978, he completed a one-year training and evaluation period in 1979, qualifying him for assignment as a mission specialist astronaut on future space shuttle crew flights.” In 1984, he successfully completed his first mission which brought his total hours in space to 191!

Dr. McNair was subsequently assigned to the space shuttle Challenger; in January of 1986 he died when it tragically exploded.

https://www.kent.edu/mcnair/life-ronald-e-mcnair

For more information about Dr. Ronald McNair:

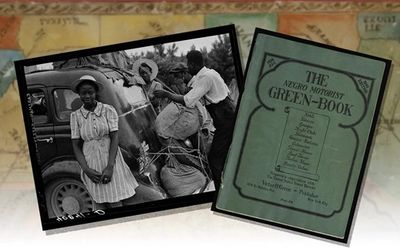

“The Negro Motorist Green Book”, first published in 1936, was an essential tool for the black motorist in the first half of the 20th century. In the American South, the early decades of motoring overlapped with the region’s most virulently racist era. Jim Crow laws mandated de jure racial segregation, and long-standing social norms not only imposed further de facto segregation, but often exacted violent punishment for the slightest perceived transgression. Black motorists were confronted by challenges largely unknown to white travelers, including when they attempted such simple – and necessary – elements of traveling as filling their gas tank, eating a meal, or finding a place to rest at the end of the day. And these difficulties went far beyond mere inconvenience. For the black motorist seeking such services in an unfamiliar region, the slightest miscalculation could suddenly turn a commonplace activity into one of humiliation, brutality, or death. The Green Book was a black traveler’s guide to safe places; it was also an act of resistance against the widespread racial discrimination of the time.

The Green Book in North Carolina

Before 1920, there was little black ownership of automobiles. But in the 1930’s, auto dealers began to advertise in black newspapers in an attempt to reach “our colored farmer friends.” The introduction of buying a car on credit helped expand ownership, including to blacks.

The private automobile offered to its owner a previously unachievable level of mobility and personal freedom. And for black people in the Jim Crow South, it offered something else: freedom from the daily humiliation of riding public transportation. Waiting rooms and on-board seating were strictly segregated for trains, trolleys and buses. And facilities for blacks were commonly inferior to those reserved for whites. A black rider who boarded a bus at the front and paid the (always white) driver the fare might be required to exit the vehicle and re-enter at the rear, where the “negro section” was located. And when seated near the dividing line between the races, a black rider might be summarily ordered to move to a different seat in deference to a white rider.

The private automobile allowed an escape from that humiliating world, so blacks found in cars a dignity that transcended a simple desire for mobility. And when they made their choice of an automobile to purchase, they often reflected another facet of the Jim Crow world they lived in: the inconvenience and danger black people routinely faced on the road. They tended to buy larger, sturdier cars that enjoyed a reputation for high reliability. Many whites saw blacks buying a large car as a simple desire to show off, or to announce that they were as good as any white motorist. The caricature of a black man driving a Cadillac became just one more Jim Crow era stereotype used to ridicule blacks as vain and infantile. But in fact, there was a quite different psychology behind a black motorist purchasing a bigger, better car. When blacks traveled the roads, there was no guarantee they would find a restaurant that would serve them; a gas station that would let them fill the tank, much less use the rest room; or a hotel at which to pass the night. A bigger car let them carry more supplies, such as picnic hampers, a portable potty, and a reserve can of gasoline. A large back seat could serve as a resting place over a hotel-less night. And quality mattered because being stranded on the road with a mechanical problem – with the local white mechanic unwilling to work on a black man’s car – might well put them in a dangerous situation. This was an era of significant Klan activity, of lynching’s for the slightest perceived provocation, and of “sundown towns” that proudly posted highway billboards saying, “Nigger, don’t let the sun set on you here.” Buicks in particular were valued for high reliability that might take the black motorist on down the road from such evils.

Black motorists were vigilant for threatening situations, knowing full well that in the event of violence, local authorities often would be of little help. Henry Shepherd spoke of traveling North Carolina roads in the 1950s and 60s:

You didn’t want to get somebody throwing something out the car window and they hit you upside the head with a beer bottle or a brick… If you reported it to the police, they he would say, ‘Ah, they’re just having a little fun.’… You have to maneuver these things because you don’t have the same rights as everybody else.

But even when black motorists could avoid physical violence, there was the constant specter of humiliation. Sidney Jones, Jr. related the story of traveling by car with his family in the 1960s. In need of gas, they stopped at a filling station that was willing to take their money but not to grant his father a shred of dignity in front of his family:

We had just come through Virginia… We stopped at a gas station. I think I was probably only nine or ten. The boy who came out to wait on us, he was about the same age. My father, he got outside the car, and he was telling him what he wanted. And the little boy said, ‘Is that all you need, boy?’

Civil rights icon John Lewis recalled how his family prepared for an automobile trip in 1951:

There would be no restaurant for us to stop at until we were well out of the South, so we took our restaurant right in the car with us…. Stopping for gas and to use the bathroom took careful planning. Uncle Otis had made this trip before, and he knew which places along the way offered “colored” bathrooms and which were better just to pass on by. Our map was marked, and our route was planned that way, by the distances between service stations where it would be safe for us to stop.

A segregated waiting room at the bus station.

In 1936, Victor Hugo Green, a World War I navy veteran and a postal worker in Harlem, New York, experienced racial discrimination when traveling by automobile with his wife, Alma. At that time, it was perfectly legal for a business to refuse service to a customer on grounds of race. Determined to help other black motorists avoid his experience, he began collecting information about businesses in his area that would serve blacks. (There had been earlier guides created for Jewish travelers, who frequently experiences similar discrimination.)

That same year, Victor Green published his “Negro Motorist Green Book”, a listing of black-friendly metropolitan New York businesses, including hotels, tourist homes, service stations, restaurants, garages, taxicabs, beauty parlors, barbershops, tailors, drugstores, taverns, night clubs, and funeral homes. Green said his intention was:

…to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trip more enjoyable.

The book was an instant success, and in 1938, Green expanded its scope to include the Midwest and most of the East Coast, including North Carolina. He received advertising support from black- and white-owned businesses. Standard Oil/Esso was extremely supportive, including selling the book at its many service stations. (Esso was a leader in pushing for racial equality, allowing black franchise owners, and employing black scientists, engineers and marketers.)

Green – and after his death, his wife – published the book from 1936 to 1966 as The Negro Motorist Green Book, The Negro Travelers Green Book, and finally, The Travelers Green Book. In 1938, the book sold for $0.25; by 1957, it cost $1.25. At the height of its popularity, the Green Book sold 15,000 issues per year, and it expanded to include international destinations, as well as to offer advice on automobile maintenance, on safe driving practices, and on the motorist’s civil rights. Whatever the full, official name of the publication at any given time, to the black travelers who relied on it, it was simply “The Green Book.”

Victor Hugo Green

Beginning in 1938, the Green Book included businesses in North Carolina, with information on eight cities: Fayetteville, Gastonia, Greensboro, New Bern, Raleigh, Sanford, Winston-Salem, and Weldon.

Among the North Carolina businesses listed in the Green Book were respected hotels in Raleigh, Durham, Greensboro and New Bern.

North Carolina Listings

Download a PDF with details about the Green Book locations of Raleigh, Durham, Greensboro and New Bern.

Green Book Locations (pdf)

DownloadThe North Carolina Transportation Museum is pleased to announce an update to the “How the West Was Won” exhibit, located in the Bob Julian Roundhouse.

Focusing on the story of Black Mountain, N.C. resident and longtime Southern Railway employee George Winslow Whittington, “The Life of a Brakeman” explains how the difficult job of brakeman changed from the era of steam to diesel locomotives. Discover the story of George Winslow Whittington, who rode the rails of Southern Railways’ Asheville Division as brakeman from 1926 to his retirement from that same role in 1963. Whittington exemplified the strong and courageous brakemen who faced many challenges so that trains could arrive to their destinations safely, a job made even more difficult by Whittington’s status as a Black man during segregation.

“The Life of a Brakeman” was created with the content curation aid of Regina Lynch-Hudson, the granddaughter of George Winslow Whittington, and contributions by his son Les Whittington, as well as other descendants.

George Winslow Whittington

The Story of Sarah Keys

Years Before Rosa Parks, Sarah Keys Refused to Give Up Her Seat on a Bus. Now She’s Being Honored in the City Where She Was Arrested.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.